FOCUS ON PERIWOUND SKIN

i

12

SKIN CARE TODAY

2016,Vol 2, No 1

As a result, chronic wound exudate has

been referred to as a‘corrosive cocktail’

or‘toxic soup’and is very damaging to

the periwound area if not contained

within the dressing (Coutts et al, 2010).

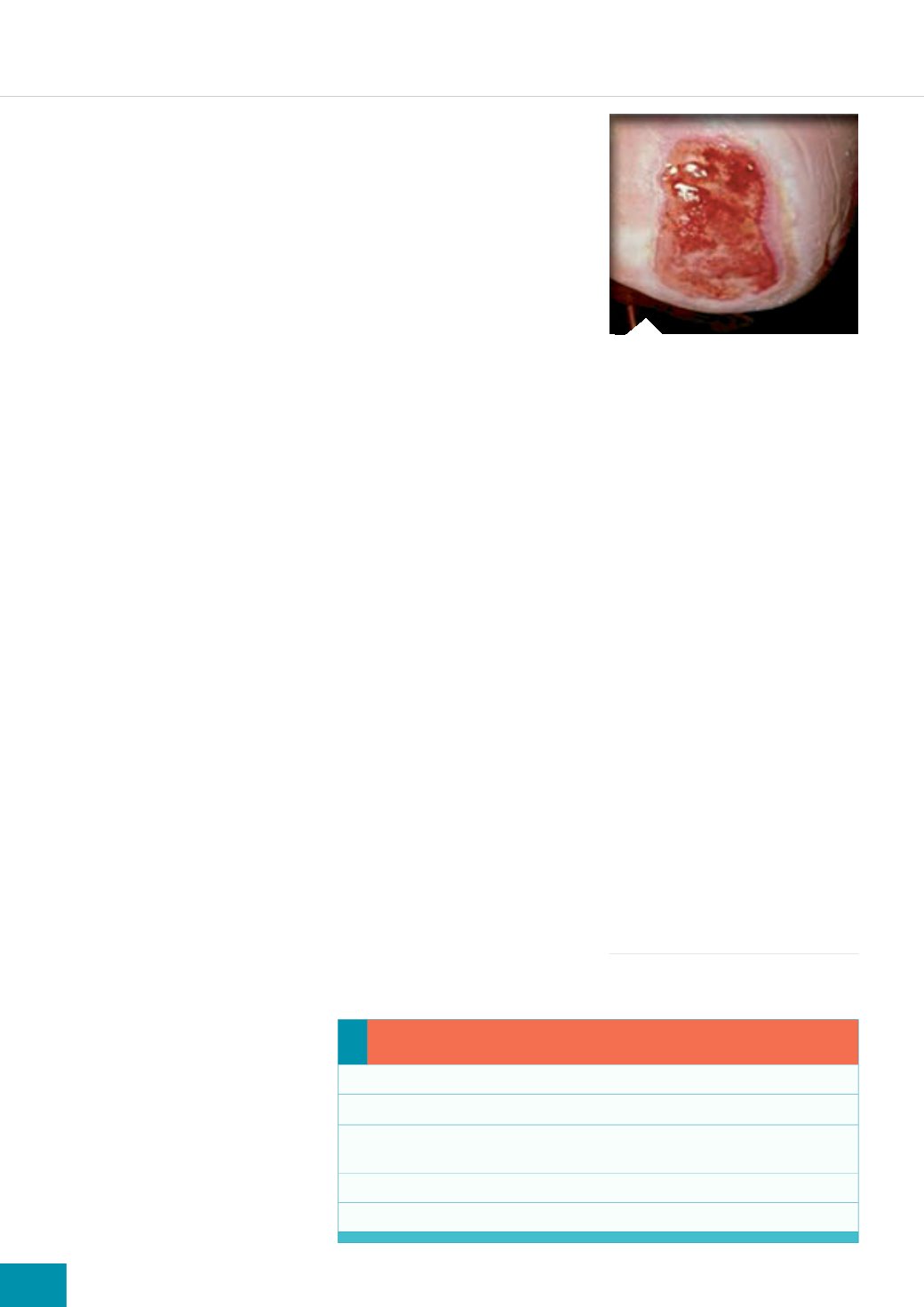

Maceration

Maceration develops when the wound

dressing is unable to handle the

volume of exudate, which, as a result,

overflows onto the surrounding skin

(

Figure 2

). It can be seen as a white

‘soggy’discolouration within four

centimetres of the wound edge and

develops as a result of overhydration

of the keratocytes in the skin and a

loss of epithelium (Cutting and White,

2002; Cameron, 2004; Thompson and

Stephen-Haynes, 2007).

A common‘everyday’ example of

maceration is that seen on the skin

after prolonged bathing, for example.

Macerated skin is weaker than non-

macerated skin and is easily damaged

by trauma and corrosive wound fluid

(Hollinworth, 2009). Macerated skin

also has a higher pH than normal

skin and is therefore at increased

risk of bacterial and fungal infections

due to the humid conditions created

by dressings (Langoen and Bianchi,

2013). It is important that nurses

understand how to protect the

periwound skin by ensuring that the

moisture balance within the wound is

well managed. Otherwise, the wound

can deteriorate and increase in size

(Mudge et al, 2008).

Erythematous maceration

As a result of prolonged contact with

wound exudate, the periwound skin

may become red, inflamed and also

shows signs similar to irritant contact

dermatitis (Cameron, 2004; Schofield,

2013). The patient may also report

burning, stinging and itching around

the affected area and the application

of a topical corticosteroid may be

needed for a few days to dampen the

inflammatory response before using a

skin protectant (Cameron, 2004). The

potency of the steroid is dependent

on the severity of the condition and

as the area improves, the potency and

frequency of application should be

reduced accordingly. Nurses should

apply any topical steroid sparingly

to the periwound area, taking care

that it is not in direct contact with

the wound, as this has been found to

delay healing (Marks et al, 1983).

Skin stripping

The repeated action of removing

and applying adhesive tapes and

dressings to the wound site will

eventually result in stripping of the

stratum corneum, the outermost

layer of the epidermis responsible

for maintaining the skin’s integrity

and barrier function (Langoen and

Bianchi, 2013).

Certain dressing types, such as

hydrocolloids, films and tapes made

of traditional adhesives are best

avoided in patients with very fragile,

vulnerable skin (Cutting, 2008).

Extra care should be taken when

treating patients who are undergoing

radiotherapy, which can render the

skin particularly vulnerable to trauma

(Goldberg and Mcgynn-Byer, 2000;

Hollinworth, 2009).

There are adhesive removal

products available on the market

that are designed to reduce the

trauma of dressing removal. Some

of these products contain silicone,

which helps to minimise the pain

and trauma of skin stripping. These

products are particularly useful

for patients with very fragile skin,

patients with epidermolysis bullosa,

or patients who experience painful

dressing changes (Stephen-Haynes,

2008). Some nurses have been known

to cut the adhesive border from

dressings before applying them as a

pragmatic solution to the problem of

protecting the fragile periwound skin

(Stephen-Haynes, 2008).

However, this is not

recommended since the dressing

will still need to be retained in

position and as Hollinworth (2009)

notes, using adhesive tape or other

film dressings to secure the primary

dressing will merely result in damage

to another area of skin.

Incorrect removal of wound

dressings can also result in skin

stripping. As a general rule, when

removing a dressing, the surrounding

skin should be supported by one

hand and the dressing gently lifted

off with the other hand; loosening

the edges first may also help and

some nurses find applying water

to the dressing edges to break

the adhesive bond helps this

process. Another strategy may be

to encourage the patient to remove

the dressing themselves; this is

particularly helpful where dressing

changes are painful. However, if pain

and trauma on dressing removal

persist, the nurse may need to

consider using alternatives such as

silicone-containing dressings, which

are designed to come away more

easily from the skin (Cutting, 2008).

TREATMENT OPTIONS

Barrier products

Traditionally, protecting the periwound

Practice points...

Periwound skin should form part of a wound assessment.

Assess exudate levels before selecting a dressing product.

Be aware that exudate levels may vary; HCPs need to change the type of

dressing accordingly.

Consider the use of barrier products when exudate levels are high.

Change the dressings according to the recommended wear time.

Figure 2.

Maceration from a highly

exuding wound.